The Brandy Report: Introduction (1/12)

In the first of our new series of reports on the global brandy sector we introduce the category - where it is now, and where it is headed.

....................................................

CLARET IS THE LIQUOR FOR BOYS; PORT FOR MEN; BUT HE WHO ASPIRES TO BE A HERO MUST DRINK BRANDY,” Samuel Johnston once remarked, apparently smiling as he did. If the British writer lived today he’d guffaw at annual brandy consumption. Measuring 178m 9-litre cases a year, it is the third most consumed international spirit in the world – there’s enough brandy to make heroes of many men.

Notably, the author of the 1755 A Dictionary of the English Language omitted brandy from his famous lexicon – but perhaps he, as commentators today, struggled with its definition.

Brandy has as many styles as it has qualities and as a result draws binary review. It is made in practically every wine-producing region of the world, and is even found in and around the tropics, a climate in which vines are not known to prosper. It’s safe to say that not all countries live by the western definition that brandy should be distilled from grape or fruit juice.

Producers in the category’s largest markets – India and the Philippines – certainly have a more liberal interpretation (one that involves a fair amount of neutral spirit made from sugar cane). But industry data researchers and commentators alike have got into the habit of rationalising that, if it is sold as brandy, it is brandy. There is a little too much brandy under the bridge to correct the record here.

So, with this malleable definition in mind, the category’s consumers too couldn’t be more different, ranging from the millions of local brandy consumers of southern India and the Philippines to cognac fans, whether they be African Americans, Russians, Nigerians or the clichéd connoisseur.

Growth

As a category, brandy is growing. Euromonitor International (which supplied all data for tables A, B and C) forecasts volume will swell 10% between 2013-2018 (see table A), maintaining its position as the third-largest international category, but this growth is coming from two major markets.

In volume terms at least, India is at the vanguard of development. As the country’s population expands and society continues to liberalise, so will its pool of drinkers (about a third of India’s 1.3bn do not drink due to religious reasons or societal stigma). In India, brandy drinking is a southern state habit (see table D), with 96.9% of the annual 61m cases of consumption occurring there, according to United Spirits estimates.

India is home to United Spirits’ McDowell’s No 1, which stumbled in 2013, shedding 15% of its volumes. At 9.3m cases it remains the heavyweight. Meanwhile, Old Admiral hoovered up sales to the tune of an 11% increase, though it is still well back at 3.9m cases.

Men’s Club’s 1,000% increase from 0.3m cases to 2.9m cases in one year was the growth story of the year – and a swing only possible among United Spirits’ moving carousel of brands. Suresh Menon, executive vice president of planning & control at United Spirits, explains how. “The growth of Men’s Club is specific to one of the states in South India, Tamil Nadu. We de-emphasised one of our brands, Golden Grape brandy, and introduced Men’s Club.” He says Men’s Club has benefitted from favourable consumer response and Golden Grape’s ‘de-emphasis’.

India is expected to increase value by 3% from 2013-2018, so will remain a low-value, high-volume market for the foreseeable. Bottle sales are likely to increase 27% over the five-year period, according to Euromonitor International, with its category share increasing from 34% to 39%.

But these projections could be derailed by Prohibition in the southern state of Kerala. An alcohol ban imposed in 2014 was later tempered after hotels and bars argued that a dry state would harm tourism. Probably the compromise will protect tourists from alcohol-free holidays and Keralans from readily available alcohol. But as India’s wettest state – reportedly 20% of the state’s revenues come from alcohol – what happens here has a profound effect on the category’s health.

The category’s second largest market is the Philippines, where 21% of the world’s brandy is dispatched. It is growing at 7%, but mostly because it is home to brandy’s skyscraper brand. Looking down from the clouds is Emperador, the Philippine brandy that has swept its domestic market with unparalleled impact. For more in-depth analysis of the market and the category’s biggest brand see page 9.

These two giant markets are strong and propelling the category forward but they are local markets that operate in almost isolation. Euromonitor International’s Jeremy Cunnington agrees. “More than any other major international category, local conditions affect brand performances. In the short term, the strong growth in its two core markets will sustain the category. However, producers need to do more to revive the category in key markets. With a lack of global brands and major support from global players it is unlikely,” he says.

Russia is the third-largest market by volume and value. As Richard Woodard discusses on page 21, it is a mixed bag of ex-Soviet state brandy and cognac and is forecast to see a 19% growth in volumes (table B) and a 27% rise in value (table C). Cunnington sees Russia – and to a lesser degree Poland – contributing to brandy’s growth in the future “due to the popularity of brown spirits and a move away from the more traditional vodka”.

The US is the only other top 10 market expected to grow (by 8%) by 2018, according to Euromonitor International. For better or for worse, brandy is in growth in its large markets, but is in negative growth in most others.

Down-traders

Traditional brandy markets are in historical decline – in Germany, Spain, South Africa and Brazil, steep decline. German player Borco reports brandy consumption is 90% off-trade and is dominated by private-label German brandy under €10. Cunnington assesses: “Germany, the world’s fifth biggest market in 2013, suffers from an old-fashioned image, with younger consumers viewing brandy as something older generations drink and thus not cool. They are turning to more international spirits categories, especially whiskies (bourbon/other US whiskeys and Irish) as well as dark rum.

“This switch by younger consumers can also be seen in other markets, particularly the emerging ones of South Africa and Brazil. The former is expected to see volume sales fall by more than 50% between 2008-2018 from 5.2 million cases to 2.5 million. As with Germany, this is due to consumers switching to more modern and fashionable products, such as whisky and vodka in South Africa and vodka and tequila in Brazil.”

“However, in some markets brandy’s decline is not entirely to do with changing consumer tastes, but also changing priorities for the producers. This can be clearly seen in China where the dominant producer, Yantai Changyu Group (84% volume share in 2013) has decided to focus its resources on wine rather than brandy, leading to an expected 7% CAGR (1.4m case) between 2013-2018.”

Cognac

Cognac is the cherry on top of the category. At about 11m 9-litre cases, the region’s entire output is a third of the size of Emperador. An arresting thought, given how much attention cognac receives. But there must be more to it than smoke, gift boxes, travel retail plinths and mirrors. Separated out brandy is more than 15 times cognac’s superior in volume terms. In value, though, cognac packs a punch. Its £10.2bn retail revenue is 69% of what is produced in the rest of the brandy-making world.

Volume for show, value for dough is the maxim of cognac. But in chasing value over volume, cognac producers have encountered other problems. There are not many arguments for a volume over value strategy, but cognac’s past few years offers one. By concentrating efforts on selling at the luxury end and not looking to necessarily build volume, cognac brands have narrowed their market and broadened their risk.

Rémy Martin is the exemplar. When China called, Rémy answered – about 47% of its sales are based in Asia Pacific. But when the XO gurgling stopped – after a crackdown on governmental extravagance – it was Rémy that was left with its finger stuck to the minus key of its keyboard.

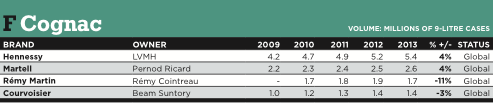

The results you see in table F (taken from The Millionaires Club 2014) show volumes, so just half of the picture. Looking at the most recent results we can see that the first half of 2014 was blighted for Rémy Martin, with a cut of 13.4% to sales value and 6% to volumes.

The group maintains its strategy of withdrawing Rémy Martin VS from the US market to continue selling older, more premium stocks. But, whatever the value or quality of the product, the group will want to lessen its dependence on the currently de-stocking Chinese market and meet demand in the booming US, Nigeria, central and eastern Europe.

Rémy Martin was not alone in the Chinese adventure. With Pernod Ricard’s distribution might, Martell was well placed to rise – and slide back down in the market. Looking at the 2013 data, the picture looks calm but a year on and Pernod is citing Martell as a key reason for its top 14 brands being in collective decline. During 2013/2014 the brand dropped back to 1.9m cases with value slipping 9% and volume 6% compared with 2012/2013.

Hennessy has broader shoulders. At more than 5m cases it amounts to about 40% of the cognac industry. With Diageo’s distribution it is the top cognac in strong markets such as the US and Nigeria. With worldwide spread, down-trading in western Europe and China was mitigated and overall declines small at -1.2% for 2013/2014 compared to 2012/2013. “With economic uncertainty prevailing in Europe, business was buoyed by a strong dynamic in the American marketplace,” read brand owner LVMH’s latest full-year report. “In China, sales of higher quality grade cognacs registered the impact of destocking by distribution channels. Hennessy partially offset this by targeting other market segments and capitalising on its rapid progress in the United States.”

LVMH added that “management of its geographic sales coverage” allowed Hennessy to “put its volumes to work for its most buoyant regions and market segments, and to leverage all of its growth prospects”.

So while Rémy Martin sought to channel its efforts into VSOP and China, Hennessy’s strategy of diversifying its cognacs, markets and target clientele, paid off.

Courvoisier is the fourth and last of the million-case brands from Cognac. Though it has strong ties to ailing Europe, it has managed steady business over the past five years while all around it has crumbled. In 2013 a small dip could be credited to weakness in Asia Pacific, but the brand is strong in the US, the top cognac market, so the growth line has evened out. Beam Suntory is yet to report on 2014, but we can expect a similar story to recent years for the brand – weakness in Asia, stagnation in Europe, strength in the US.

Elsewhere among the world’s million-case brandies is Dreher in Brazil. Owner Gruppo Campari said its Brazilian business grew 4.9% in the first three-quarters of 2014, thanks to the brand. Its 2014 performance is expected to rally against what has been a flat past five years.

Brandy is a global category but largely it is local-market dynamics that set the growth agenda. The following pages seek to explore these top market trends and the big brands’ current and future prospects – be it domestic or international.

The Brandy Report comes in 12 parts. Folllow the links here Category introduction by Hamish Smith (1/12), Brandy in the Philipinnes by Hamish Smith (2/12), Cognac by Nicholas Faith (3/12), Premium brandies by Richard Woodard (4/12), Armagnac by Ian Buxton (5/12), French brandy by Hamish Smith (6/12), Spanish brandies by Dominic Roskrow (7/8)