Flavoured beer masterglass

Jeff Evans looks at how brewers are enjoying the new freedom of the craft movement to experiment with all manner of ingredients

_________________________________________

At a time when beer is enjoying unprecedented popularity and consumers are constantly demanding new and interesting drinks, barely a day goes by without the arrival of something eye-catching and exotic on the bar. Brewers today enjoy a liberty to experiment not seen for many a year and, increasingly, this is leading to the development of some unusual flavours during the brewing process.

Flavour in a beer is primarily derived from four basic sources. First there is the malted barley that, depending on how deeply it is roasted, can provide notes of anything from biscuit to coffee. The malt is balanced by hops, which, according to the variety used, can add flavours as varied as herbs and citrus fruit. The water used to bring the malts and hops together may also have an influence, as its minerals come to the fore. Finally there is the yeast, which not only converts sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide but also generates fruit, floral and other characteristics. It’s a complex set of tastes and aromas that the skilful, experienced and imaginative brewer can harness to create a fantastic product.

But, not content with these four primary flavour generators, some brewers also reach out to other ingredients or adopt unconventional techniques to take the sensory profile of their beers in other directions. The use of such additional flavourings in beer is nothing new.

Before hops were adopted some 400 years ago as the main means of providing a bitter balance to the sweetness of the malt, brewers incorporated all manner of herbs and spices to achieve the same effect. Commonly in use were anything from bog myrtle (sweet gale) to yarrow and the mix of such ingredients was called gruit.

Some breweries still play around with the kind of ales this created, most notably the Gruut brewery in Ghent, Belgium, which offers several types of unhopped beer, and Williams Bros in Scotland, which has enjoyed many years of success with beers featuring heather (fraoch), pine sprigs (alba) and even seaweed (kelpie).

Although the days of gruit are mostly in the past, spices have never left brewing. Ginger beer is an obvious example, the lemony accent of root ginger and the warming kick it provides now being welcomed by many brewers – Italy’s Doppio Malto, for instance, with its Zingibeer. Some brewers are even more adventurous. Hop Back in England has been producing a beer called Taiphoon since 1999. Featuring lemongrass and coriander, it was devised to be the perfect accompaniment for an oriental dinner, but its perfumed fruitiness is very refreshing even on its own.

ADDITIONAL FLAVOURING

Historically, there was often another good reason to opt for some kind of additional flavouring. In those pre-refrigeration, poor-hygiene days, beer often turned sour rather quickly and a crafty dosing of something pungent could just about make things palatable. That may have been how the Belgian witbier style came into being, with its lacing of bitter orange peel and coriander – both in handy local supply thanks to the seafaring Dutch and their trade in exotic ingredients. Among the best-known examples of this spicy, fruity beer style today are Hoegaarden from Belgium and Hitachino Nest White Ale from Japan.

Sourness may also have been the reason other Belgian beers are flavoured with fruits. The names kriek and framboise/frambozen are commonly bandied about by beer enthusiasts,  referring to beers that are boosted with cherries and raspberries, respectively.

referring to beers that are boosted with cherries and raspberries, respectively.

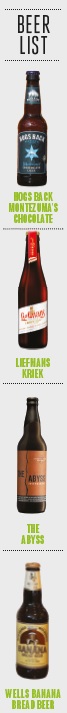

In the most authentic instances, the beers are partly fermented with these fruits, too, the additional sugar they provide helping to generate a secondary fermentation as the beer sits in casks or tanks at the brewery, ripening with age. These beers are naturally acidic and tart because of the infiltration of harmless bacteria as they mature, but the fruit notes provide a distraction and bring some sweetness. Fine examples include Liefmans Kriek Brut and Boon Kriek.

Fruit is also on the menu for producers elsewhere in the world, some using it to enhance the often-strident citrus notes of American hops. The award-winning Lemon Dream, for instance, from the Salopian Brewery in England, is a zesty golden ale that features organic lemons, while Ballast Point’s Grapefruit Sculpin from the US is an IPA with added grapefruit.

Some brewers use fruit to build on beer’s other inherent flavours. Charles Wells Banana Bread Beer has been around for more than a decade. The added bananas complement the toffee notes of the malt to create a banoffee pie effect. Both Stewart Brewing in Scotland and Maui in Hawaii produce coconut porters that are the liquid equivalent of a Bounty bar.

Honey is another long-serving brewing ingredient. Like fruit, it adds to the fermentability of the brew and brings its own flavours, especially if very floral honey, such as lavender or chestnut, is used. Honey also changes the texture of a beer, delivering a very soft mouthfeel, particularly on the swallow.

The Septem microbrewery in Greece produces an excellent honey ale called Sunday’s, while one of the most successful honey beers is Fuller’s Organic Honey Dew from London.

More recent additions to the brewer’s larder have been chocolate and coffee. When you consider just how much chocolate and coffee flavour some beers naturally present, because of the dark malts with which they are made, this is an obvious move, often resulting in a vanilla creaminess or a richer roasted character.

Pioneers in this field were London brewer Young’s with its sumptuous Double Chocolate Stout (now brewed by Charles Wells) and America’s Samuel Adams with its Chocolate Bock, which is aged on a bed of cocoa nibs. A newer, innovative take comes from Hogs Back, whose Montezuma’s Chocolate Lager is deceptively golden in colour. Founders Breakfast Stout from the US is just one of many noted coffee beers percolating today, or try Beer Geek Breakfast from Denmark’s Mikkeller brewery.

TIME FOR TEA

If you’re going to use coffee in a beer, why not tea as well? It won’t work in the same sort of dark, malty brew but there are beers to which it can add something special, particularly those that have a hop character that the tea can enhance.

England’s Marble Brewery does this rather well with its Earl Grey IPA. The brewers realised that some beers can have a tannin-like astringency, similar to that found in tea, and also that certain hops naturally have a tea-like flavour. Earl Grey tea is itself flavoured using bergamot, a variety of orange, so it has a delicate fruit note. When you marry this with the citrus accent of certain American hops, the result is both clever and convincing.

One of the biggest ideas of recent times has involved ageing beer in oak although, again, this is a practice that was common centuries ago. For various reasons – not least the need to improve cash flow and save valuable space at the brewery – the idea fell out of favour during the 19th century.

As with the fruit beers mentioned above, the process would have created a notable sourness as natural bacteria worked their magic and great examples of this style of oak ageing thankfully still exist in the form of Rodenbach Grand Cru and Verhaeghe Duchesse de Bourgogne from Belgium, two highly-refreshing, tart beers that have been made this way for many decades.

As today’s adventurous brewers are finding, even where bacteria do not play a part, this ageing process slowly reduces the influence of the hops and allows instead the tannins and creamy vanilla notes of the oak to come to the fore, adding a new dimension to the beer.

Often the casks have been used for storing a spirit before the beer is introduced. The flavour of the spirit then tends to shine through so some beers really can have a strong whisky or brandy taste. Scottish brewer Innis & Gunn specialises in this field, with a range of beers with different ‘finishes’, including Innis & Gunn Rum Finish and Scotch Whisky Porter. From the US, Goose Island’s Bourbon County Stout and The Abyss from Deschutes – an imperial stout that is aged in both bourbon and Pinot Noir casks – are other highly acclaimed beers.

Some brewers cut out the casks completely and just use stronger liquor as an addition on its own. Wadworth has a rum beer called Swordfish, brewed initially to commemorate 100 years of naval aviation in the UK and spiked with the rum that was once rationed daily in the Royal Navy.

Beer is such an accommodating drink – it can be sweet, bitter, light, heavy, malty, hoppy and much more – that any number of additional ingredients can be used to enhance its natural flavours and take it to a new level. There are lagers with the burn of chilli, stouts enriched by liquorice, strong ales sweetened by treacle and many other such creations. I don’t think we’ve yet been treated to an aniseed amber, a mustard mild or an elderberry export but it can only be a matter of time.