The Making of Muldoon

Sean Muldoon – owner of New York’s Dead Rabbit and Black Tail – takes Hamish Smith back to growing up in the Belfast troubles, joining the Foreign Legion, and being Eminem before Eminem

________________________________________________

"I’VE SEEN MAD things in my life. I’ve seen bullets fly, bomb blasts and shrapnel dancing about the street. In Ardoyne, north Belfast, this was an everyday occurrence during The Troubles. You believed you could be shot from the minute you got up to the minute you went to bed. Even at night, you believed you could be shot in your sleep. Ardoyne is where the shit went down. You were guilty because of where you lived. All I wanted was for people to learn to live together,” says Sean Muldoon.

As far back as he can remember, Muldoon wanted out. The politics and violence were suffocating – his only escape was his imagination. “I was a dreamer. I grew up watching Hollywood and I was inspired by rags-to-riches stories. I always believed anything is possible but you had to go out and get it. At that time, opportunity was never going to come to Belfast.”

Muldoon says there was “anger” in him – at his situation, at his lack of options. The army – as a means to vent and escape – appealed throughout his teenage years. But it wasn’t as simple as signing up. “The Irish army was preferential to southern Irish people. If you joined the British Army you’d be burned out of your house. So I went and joined the Foreign Legion.” Muldoon, among the rag-tag mercenaries in southern France, lasted a week. “It was when I was being commanded in French that it hit me – I was going to fight and potentially die for France. Why the fuck would I want to die for France?”

Muldoon was lost. “I’d told all my friends I’d gone to join the Foreign Legion and then I was coming back after a week. I had no education, no direction but I knew in my head I’d find my way. I had always dreamed of being a film director – I can write and I have an imagination and could see myself behind the cameras – but that meant further study and I just wasn’t disciplined enough. I was also interested in music.”

MEANS OF ESCAPE

When Muldoon returned it was to produce an album. “My mates laughed their heads off. They thought I was bonkers.” But the idea rattled around Muldoon’s head. “I told myself: I’m going to make a CD. It’s going to be my escape.”

But he needed space to think and money to fund studio time. He ventured out to his version of a creative retreat – a bar job with free accommodation in a three-star hotel in rural Scotland. It didn’t start well. “After five weeks I was told I’d be fired unless I got with the programme,” says Muldoon.

Ever the thinker, he set out into the Scottish wilderness to ruminate over his future. Did he have the discipline to see this bar job through? Would his dreams of producing music come to fruition? And where was he going to sleep in the middle of the Scottish countryside with no money? “There were no cash points so I had to sleep rough for two nights. I found somewhere near the house of Robert Louis Stephenson – I remember seeing the plaque.” When Muldoon returned to the hotel it was to give it his all. Within months he was the bar manager and stayed in Scotland for a year and a half, saving up £7,000.

Back in Belfast, Muldoon took a makeshift job at his father’s social club, where he met his wife, Anne, and, with the money made from a pennywise existence in Scotland, started recording what was written in his head. Muldoon’s music was lyrical, stylised and angry. One song was called The Gun. “Everyone in Belfast used to talk about how the guns do the talking. In my song the gun tells the story as if it has a mind of its own. At the end you realise it’s not the gun owner in charge but the gun. The gun gets pointed back at him… It’s an Americanised interpretation of the Belfast troubles.” Was he inspired by Eminem? “This was 1995, before Eminem, but I remember my sister saying to me that there’s this new guy that sounds just like me – this was when Eminem came out with Stan.”

Muldoon’s songs had started to get airplay but it was bartending that paid the bills. In Muldoon’s neighbourhood, bars carried nicknames – there was the Suicide because it was such an open target – and his bar, the Clifton Tavern, carried the moniker the Sitting Duck. It had no security gate, no intercom and no chance if it was hit. By now, in 1996, the ceasefire was taking hold, but the murder of prominent loyalist Billy Wright had seen a spate of revenge killings in his part of town. “It was chaos. Every catholic who moved was a target.” Worrying times to be working at the Sitting Duck.

“When I opened the bar on New Year’s Eve in 1997, I just knew something was going to happen. There had been 11 or 12 murders. I had my secure walking routes to get to and from the bar, but inside I felt seriously vulnerable. I said to the owner: ‘What are you doing about security?’, he said: ‘Staying the fuck out of here.’ I could feel we were going to get hit, from my toes to my head.” Muldoon’s shift finished at 7pm and two hours later bullets were sprayed into the bar. Two people lost their lives, five others were injured.

Muldoon was down and wanted out – but he didn’t know how. Inspiration came from the most unlikely source. “I watched a TV programme about an Italian carpenter – a Jesus-type character – and how he became one of the most sought-after furniture makers in the world. I thought, how do you take something so basic and make it so monumental? I remember looking at the doorman at the bar and thinking: he could be the bodyguard for the president of the US, but he’s a doorman. It’s his choice. It made me think of my father who worked as a wood joiner. He never believed in himself.”

CHOSEN CAREER

“I decided I wanted to be the best fucking bartender in the world. My friends laughed – they thought I was a lunatic.” Muldoon’s mind was made up, but beyond serving pints and shooters, he didn’t really know how to bartend. “Someone said I should check out Jas Mooney’s place, Madison’s. “I was used to bars where the doorman wanted to fight you, the coffee was Nescafe and the wine had been open for six weeks – but this place… the doorman was wearing a polo neck and welcomed me as I entered. They had espresso machines and the bartenders wore Mandarin-style outfits. It blew my mind and I decided right there I wanted to work for this guy.”

Muldoon took as many training courses as he could afford, but still had zero experience of this sort of high-end bar. “The guy who interviewed me was familiar with the Clifton Tavern situation and he sympathised. He saw something in me and gave me the chance.”

Muldoon took it. He absorbed the advice of mentors Mooney and well-travelled bartender Morgan Watson and took regular trips to London, visiting the best of the bars. He started to create a name for himself in the emerging Belfast cocktail scene and eventually turned consultant, writing menus for new Belfast bars that would go on to win UK-wide awards.

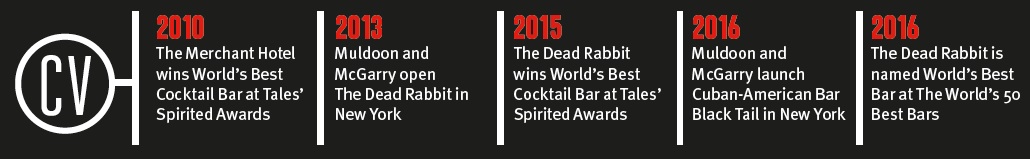

In 2006 Muldoon was offered a chance to create his own cocktail bar – the now-famed Merchant Hotel in Belfast. He knew exactly what he’d do. “The Merchant was inspired by my two favourite London bars: Salvatore Calabrese’s Lanesborough and Milk & Honey. I wanted to create a proper cocktail bar in a hotel for the first time.” By 2009 The Merchant, under Muldoon and the then precocious Jack McGarry, won World’s Best Hotel Bar at Tales’ Spirited Awards, then World’s Best Bar in 2010. It was unheard of for a bar outside New York or London to achieve such international accolades. But Muldoon and McGarry didn’t just want to form a strong team at home – they wanted to do it away.

The opening of Dead Rabbit in New York meant Muldoon moved from Belfast at the ripe age of 39. In the five success-strewn years since the opening, his drive and imagination have seen him become one of the most important figures in the bar business. His Belfast friends don’t laugh now.